Knowing that drugs and other surrounding influences were inevitably going to be his downfall, Bowie left the party life of Los Angeles for Berlin in 1977. This was the Berlin before the wall came down, and the city was to be both his refuge and his self punishment. It was to give him the obscurity and space he needed to find perspective, to heal, and to work.

Knowing that drugs and other surrounding influences were inevitably going to be his downfall, Bowie left the party life of Los Angeles for Berlin in 1977. This was the Berlin before the wall came down, and the city was to be both his refuge and his self punishment. It was to give him the obscurity and space he needed to find perspective, to heal, and to work.

He settled with his wife in a particularly austere part of the city, and he immediately went to work. Bowie along with Tony Visconti, Brian Eno, and others began recording sessions in Hansa Studio, which looked out on the famous wall. They entered the studio to create and to excavate, but not necessarily to produce an album. Rather, they hoped an album would arise from the expression, but the album was not the goal: music was.

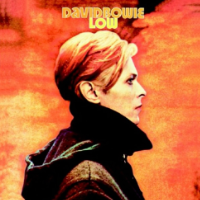

The result was Low. Coming from the rocker Bowie, the somber music of Low defies categorization into a neat genre. Due in large part to the influence and foundation of Eno’s sublime ambient music, Bowie’s Low creates a tapestry that is both luxurious and subtle. The sound carries upward Bowie’s angst, his hopeful sadness, his disappointment, and his pain, bearing it to an evident but very subtle hopefulness. Through this album, you can sense Bowie’s self-healing—going from despondent to hopeful, from lying down to sitting up, and ultimately ready to regroup his energy.

The result was Low. Coming from the rocker Bowie, the somber music of Low defies categorization into a neat genre. Due in large part to the influence and foundation of Eno’s sublime ambient music, Bowie’s Low creates a tapestry that is both luxurious and subtle. The sound carries upward Bowie’s angst, his hopeful sadness, his disappointment, and his pain, bearing it to an evident but very subtle hopefulness. Through this album, you can sense Bowie’s self-healing—going from despondent to hopeful, from lying down to sitting up, and ultimately ready to regroup his energy.

This healing prepared him for what came next: the still experimentally moody but far more positive and energetic “Heroes” that came out later the same year.

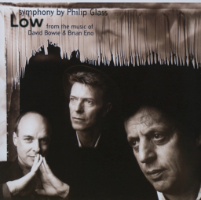

Fifteen years later, in 1992, successful avant garde composer (let’s please not call him a minimalist) Philip Glass reinterpreted three tracks from Low as his first symphony. It is a magnificent work, but understanding the sadness and bleakly desperate need for revitalization that Bowie infused into Low makes Glass’ reinterpretation even more stunningly remarkable.

Take, for example, the track “Some Are.”

Bowie wrote this piece in Berlin with the other tracks, but only included it in a later release of the album. Just over three minutes in length, Bowie’s “Some Are” is slow and sombre. A slow, plodding thrum in the 3/4 time of a waltz is backed by the subtle sound that is difficult to place: perhaps it is a hint of distant children playing? There is the barest hint of hopefulness in Bowie’s voice when he begins to sing, just as, in a bleak winter scene, a ray of sunlight reveals sparkling in the snow. This is the quiet song of someone who has resigned himself to melancholy. The sampled sound reappears again at the end of the piece. At first it sounds again like the children, but now you cannot help but hear that this is actually the sound of distant yipping and yammering coyotes.

Glass’ interpretation picks up on the single ray of hopefulness in Bowie’s voice and turns it into the driving motivation. Where Bowie’s piece begins with the plodding thrum, Glass doubles the note and applies his signature use of repeating arpeggios to give it energy. Instead of a somber, plodding piece, now it is an exuberant, joyful skip. Instead of subtle distant animalistic sounds, there is a scaling of music, carrying the once melancholy melody to nothing short of exuberance. Where Bowie’s voice revealed a single ray of hope in a bleak landscape, Glass’ strings call forth brilliant sunshine. The winter snow is gone, replaced by verdant spring.

Glass’ interpretation picks up on the single ray of hopefulness in Bowie’s voice and turns it into the driving motivation. Where Bowie’s piece begins with the plodding thrum, Glass doubles the note and applies his signature use of repeating arpeggios to give it energy. Instead of a somber, plodding piece, now it is an exuberant, joyful skip. Instead of subtle distant animalistic sounds, there is a scaling of music, carrying the once melancholy melody to nothing short of exuberance. Where Bowie’s voice revealed a single ray of hope in a bleak landscape, Glass’ strings call forth brilliant sunshine. The winter snow is gone, replaced by verdant spring.

Where Bowie’s piece ends at just over three minutes, Glass goes on from there. Having turned the bleak vista into a lush joyful landscape, he adds a movement that inhabits it quietly, almost as quiet and slow as Bowie’s original, but without the melancholic mood. In a video in which the two musicians discuss the piece, you can see Bowie’s delight in Glass’ re-imagining.

Here are both Bowie’s and Glass’s versions of “Some Are.”

In a world where far too many gifted artists succumb to drugs and suicide, Bowie looked his despair square in the face and refused to let it take control. His Berlin Trilogy, beginning with Low, was the result of his battle to win back his life. Where Low is an overt outward expression of his pain, Glass’ incredibly positive, exuberant, and delightful interpretation expresses a confident resolution of that pain. Just as Bowie triumphed over his emotional angst, Glass’ Low tells the end of Bowie’s Low story.

The end of this story

I was one of the very few young party-brats in the 1970s who was not a huge fan of David Bowie. It’s not that I disliked his music, I just wasn’t aware of it against the backdrop of King Crimson, Yes, and the others I was listening to. It was actually through my appreciation of Philip Glass well into my adulthood that I came to appreciate Bowie at all, although, other than Low and “Heroes” I’m still not what I’d call a fan.

I wrote the first draft of this blog post on January 29, 2016. I was on a plane, heading to Boston to see a concert with my brother, Tim, at the Kresge Auditorium on the campus of MIT. “An Orchestral Tribute to David Bowie” was a performance of Glass’s 1st and 4th symphonies (both based on Bowie albums). The event was arranged to pay tribute to David Bowie, who had died of liver cancer just 19 days earlier in New York. All of the musicians were local amateurs, as opposed to an organized symphony, and the proceeds went to fund cancer research.

It was a deeply moving performance. I think Bowie would have loved it.