This is a guest post by my partner, Dave.

In 1943, James Wright found himself standing in a General Electric laboratory in Connecticut, staring at a blob of goo. He’d been trying to make artificial rubber.

The war effort couldn’t get enough natural rubber for the tires, gas masks, and boot soles that it needed. James, a chemical engineer, had been trying to invent a synthetic rubber replacement.

His latest batch was yet not quite right.

The stuff was gooey, bouncy, and stretchy. It broke into pieces if you hit it hard enough, then pooled back together like nothing had happened. But it would not hold its shape under pressure.

The U.S. Government could not use it. For several years, James handed out samples of the material to other scientists and to friends as a curiosity. But nobody could find a good use for it.

Then Peter Hodgson saw it at a party.

Peter was a marketing consultant for a toy store. He watched adults play with the strange gooey substance, laughing, stretching it, bouncing it off tables. Then he realized its potential.

Peter bought the production rights from GE for $147 and packaged the stretchy, bouncy putty in plastic eggs because Easter was coming.

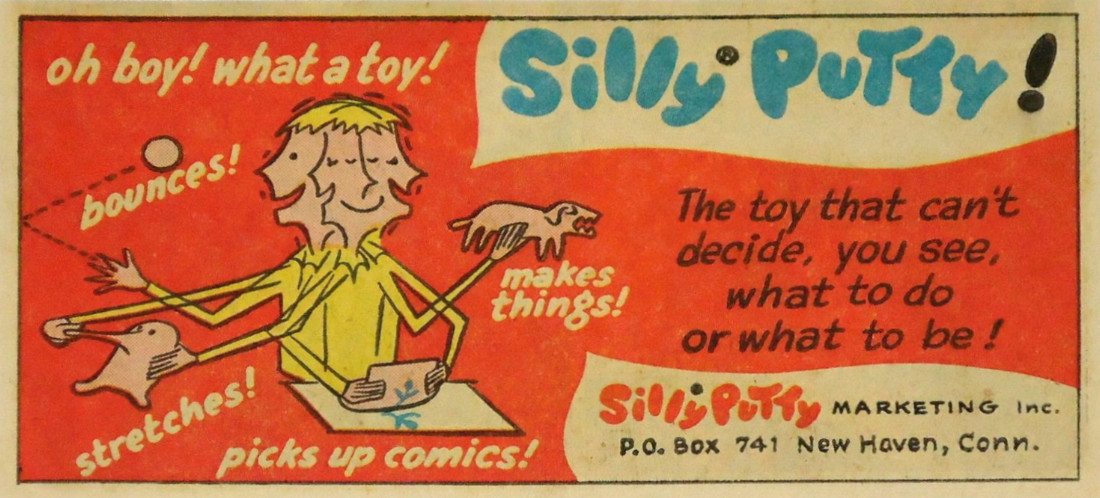

He called it Silly Putty.

By the end of 1950, Silly Putty had outsold almost every other toy in America. Peter died in 1976 with an estate worth $800 million in today’s dollars, an estate almost entirely built on goo.

There’s more. In 1968, the Apollo 8 astronauts carried Silly Putty in their journey around the Moon, where they used it to keep tools from floating in weightlessness. James’s failed experiment made it to the moon.

When you make something that doesn’t quite work, maybe you haven’t yet found the right egg to put it in.

(But wait! There’s more: keep scrolling…)