In the mid 20-teens, my father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. By that time he was already starting to have mental slip-ups, enough that when he received the diagnosis, he seemed to promptly forget it. After twice having to tell him that he had the disease, my stepmom decided that maybe he didn’t need the reminders and just let it go.

In the mid 20-teens, my father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. By that time he was already starting to have mental slip-ups, enough that when he received the diagnosis, he seemed to promptly forget it. After twice having to tell him that he had the disease, my stepmom decided that maybe he didn’t need the reminders and just let it go.

About that time, I came for a visit. We’d always been very close, but now I felt like the clock was ticking on what I could learn from my Dad about his life. Wanting to get as much quality time with him as I could while he was still himself, I took him out to dinner.

Over the meal I tried to engage Dad in reminiscing about his childhood and his life. The conversation eventually veered into my Grandpa’s final years, in which he had descended into that unpleasant flavor of Alzheimers in which the patient turns into the antithesis of himself. I hadn’t thought ahead to this conversational possibility so felt overwhelmed by the irony as my Dad, with his shiny new but forgotten diagnosis, talked about his always-cheerful and caring father who ended his days with much anger, crudity, and violence.

“If I ever got that disease, I’d absolutely want to go — you know, I’d want to just end it,” Dad said.

I was stunned. Silent. I mean, I wasn’t at all surprised this was how he felt, even though we’d never discussed it. But now that he had Alzheimer’s and was already so far into it that he was having some pretty significant memory lapses, what could I do with this statement?

I suddenly felt a very deep responsibility. Dad had repeatedly forgotten that he had Alzheimer’s, yet here he had told me that if he ever got it, he would want to be sure to take his own life: to die his own way instead of the horrible disintegration into indignity that is Alzheimer’s. He told me this, and now I wondered: should I tell him: “Dad! You have Alzheimer’s right now! If you want to end your life, you’d better do it soon or you will be too far gone to do it or to even know that you want to!”

It was a terrible responsibility. I stared at Dad. Did he know and was waiting to hear what I’d say? Was this a test? Only seconds had gone by, but it felt to me like time had stopped.

“Do you want that last piece of bread?” he asked. He picked up the bread and resumed our conversation.

Soon we were talking about his yard (his favorite subject), his recent move to Phoenix, and all manner of trivialities that signaled that we’d clearly moved on. I felt like I’d both dodged a bullet and let my Dad down in the most intense possible way. But I realized that his current situation hadn’t been in his mind at all, or if it was, it was already long gone. Unreachable. It was too late for him.

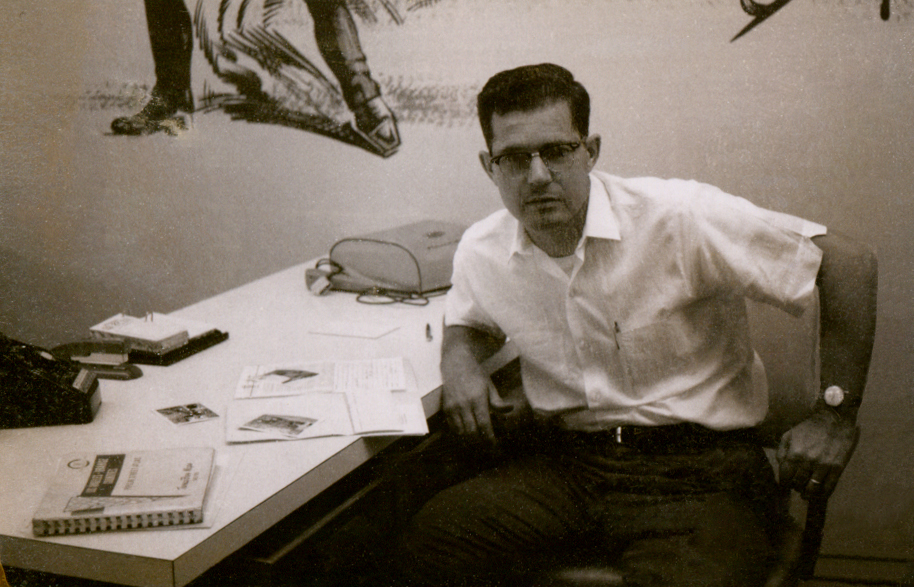

Now, several years later, when I think about that evening it deeply haunts me. My wonderful father is now barely still there. He is a small shadow of his former self, although still very much him, recognizable to those of us who knew him and know what to look for. He’s still trying to make himself useful, still feels some purpose to take care of the yard, but he’s fading… slowly, slowly going away right before our eyes.

My family is phenomenally lucky that Dad’s disease has gone the easier route of fading him into blissful innocence, not the harder road my Grandpa travelled. But already, Dad’s just waiting: he’s killing time until time will finally kill him. And sometimes, he knows it. At odd moments of near lucidity, he’ll say things like, “You know, I’m a very old man now. Pretty soon I’ll be over.” Soon he will fade into a tiny wisp of remaining selfhood that will get dimmer by the day, held to this earth in the failing, undignified body of a frail old man who is waiting to die.

I’m so sorry, Dad, that I didn’t tell you that night what your sad fate was and what ending had been decided for you. If I had told you, would you have done something about it? Would you have gone home and looked for pills, or headed out to a busy street and stepped into the stream of traffic? When I wonder about this, which I do often, I think you wouldn’t have. I think by the time we shared that moment at dinner, you were already just far enough gone that you wouldn’t have had the mental capacity to do it in the short time you had before the knowledge of it slipped away. But I don’t know.

And now, as I watch you wait to die, I can only tell you over and over again, albeit only in my mind, how very sorry I am that I failed you.

[More posts about Alzheimer’s]